Monday, April 12, 2010

The World Is Made Of Stories

These days I look for stories everywhere. I love language, have made it my life's work. I have spent much of my work years with children at the beginning of their language journey. It is an amazing process -- semantics, syntax, pragmatics. The dance of language starts young, from birth, long before the first words come. And it seems, at least to this storyteller, that stories begin far earlier than a child tattling on a brother or sister, repeating a favorite story, beginning "once upon a time." Sometimes a point, a demo, one word and a laugh conveys a wondrous tale of a toy, a pet, a parent.

Yes , communication is my work and my joy. To me, language seems a miracle every time a child moves from first word to phrase, from phrase to sentence, from sentence to monologue and dialogue. The books insist language is purely the provenance of man. The dance of bees, birdsong, animal calls communicate but aren't language. And yet, we learn things that blur the edges, make us think maybe language is not just ours, what makes us different from the animals, "better."

I love crows. They are amazing, fascinating, intelligent creatures. They possess a strong family connection, a rich and varied social structure, tool use, cause and effect. They possess a "language" they use with close family and a different one they use within their intimates. But according to a documentary I saw at the Santa Barbara International Film Festival, A Murder of Crows, crows communicate with their progeny, teaching them at least about dangers, finding some way to describe the attributes of a face of someone that threatened the nest (crows apparently possess amazing facial recognition).

Now I read about Gunnison's prairie dogs, some of the most sophisticated communicators around. Yes, communicative prairie dogs. Is it language? Maybe. Are they telling stories? Okay, I'm a bit of a dreamer but I would say, maybe.

Here's what we know. These little guys possess a very sophisticated social structure. They live in "towns" for God's sakes, and this is not just a colorful phrase. It's not just biological families of prairie dogs hanging together, although there are groups or corteries that consist of biologically related members. There are also groups with a dominant male and a harem of females and progeny. And there are groups where unrelated males and females live together and defend territory. Not so different really from human towns where non-familial bonds can be just as strong as familial bonds.

But back to language and stories and prairie dogs. Prairie dogs, apparently possess complex predator warning calls. This in itself is not suggestive of language. Lots of animals possess predator warning calls. That doesn't make them language. Here's the difference. These calls are not instinctual but taught over time. Animal behaviorist, Con Slobodchikoff, and his team have been recording prairie dog cries and have found young prairie dogs don't know these cries at birth but are taught them, a process of learning and physical maturity. But here's the cool thing. The cries are not a universal warning, but predator specific, so the call warning of a black-footed ferret differs from the cry warning of the Ferruginous hawk which differs from the call warning of a badger, which differs from the cry warning of a human with a gun taking target practice. This is unique, but it gets even better, for Slobodchikoff has discovered that prairie dog whistles and cries denote in a short communicative burst both adjectives and nouns. They don't just identify the predator but contain information about the enemy's size, color, direction of travel and speed. So the chirps and whistles we hear could be saying, "A tall, skinny coyote is moving quickly in the distance," or describing another predator in rather specific detail.

Are they telling stories? Probably not. A prairie dog telling a story about a hawk, a badger and a ferret entering a bar is probably not imminent. Still, there is something thrilling about these discoveries of languages we hardly guess at, that hint of so much more we don't know. A world of discovery exists all around us, what we know miniscule to all we don't. The world is full of stories, about tall, skinny, fast moving coyotes, about fearsome-faced intruders that cannot be trusted, about an orphaned girl who works like a servant for her cruel stepmother and stepsisters, dreaming of a prince and happily ever after.

That's how the world looks when you grow old enough again for fairy tales.

Sunday, April 4, 2010

Hungry For Your Love - Zombie Romance? It Could Happen.

Years passed. She did write although it took her years to finally submit her work. She did get published in literary journals. If you had asked her about being the "voice of her generation" she would have laughed. That was a child's dream, not a woman's. Still, she wanted to write good stories, stories that spoke deeply, sometimes in whispers, sometimes in screams. And she wanted a story of hers in a book, something you could buy at a local bookstore, something you could hold between your palms, turn the pages.

I was recovering from bypass surgery. Medicine would say I had recovered. My scars were healed; my sternum knitted. My cardiologist approved my full-time return to work and told me I wouldn't be seeing her anymore. I didn't have a lingering heart condition. I could followed by my doctor. I was "cured." Whether I was fully healed or not was a different matter entirely. The knitting of my soul would take many more months. A year later, it's still healing.

A friend sent me the link to a call for short stories for a Zombie romance anthology. I had four days to write a story. I don't write short stories in four days but I did this one. Luckily for me the emphasis was on romance, not steam. I was in a sweet, contemplative place, hopeful about love and the future in a way I hadn't been in a long time. So I wrote a sweet story, the woman who has nearly given up on love, a zombie who is trying to find his place in the world, his way, out of touch, stumbling, fumbling.

Two months later, sure my story had not been accepted, I got notification that it was going to be included in the anthology. A favorite author of mine, Francesca Lia Block

Is it an important story? Hard to know. It was the story I wanted to write, my story. I think that was critical, is critical to anything I write. Maybe a story will get published or maybe it won't, but the story has to be mine, has to be what I want to write. Does it speak deeply to something in the reader? To some it speaks and I can't tell you how much that means to me. This postmodern world is too fragmented for one voice, but I am happy to be one of many.

"Through Death To Love" is not the story I imagined as my first published tale. If you had looked at this Penelope's tapestry, you would never have seen Hungry For Your Love woven into the fabric. I had to unravel my story and re-weave it into this new one, again and again, not to put off suitors, but to make it fit, get it right, at least for now.

I'm trying to learn that life sometimes knows better than me. "Through Death To Love" has been such an important lesson about the sweetness of life, enjoying the happy surprises, and accepting that my way isn't the only way, sometimes isn't even the right way. Maria Tatar writes that fairy tales hold lessons within them. I suspect they hold lessons without as well, in the writing of them, in how they find their readers. This is the wonder of fairy tales.

Sunday, March 7, 2010

How Do We Read A Tale?

Oh lucky the paper that can include, and does, articles about fairy tales. That they're written by A. S. Byatt makes the reading sweeter. I stumbled upon these articles after I had finished my first post-bypass fairy tale. They were different, these new tales, from the first ones I attempted. It's hard to explain, exactly. Maybe you could get a sense of the difference in reading them. There was something more inclusive and yet more liminal. I was both character but also audience, I was telling the tale and listening, al at the same time. And I was making them mine.

Oh lucky the paper that can include, and does, articles about fairy tales. That they're written by A. S. Byatt makes the reading sweeter. I stumbled upon these articles after I had finished my first post-bypass fairy tale. They were different, these new tales, from the first ones I attempted. It's hard to explain, exactly. Maybe you could get a sense of the difference in reading them. There was something more inclusive and yet more liminal. I was both character but also audience, I was telling the tale and listening, al at the same time. And I was making them mine. Sunday, January 31, 2010

Writing Our Lives as Fairy Tales, Redoux

I find a connection with a new friend -- the filmmaker Guy Maddin. He tells me, "If you can find the story about Guy's third birthday party and the monkey, you need to. It's hilarious." David has rubbed elbows with Guy. He's probably heard the story from Guy's lips, as opposed to second-hand. It may be an apocryphal tale in every way --hidden, esoteric, and spurious -- but that doesn't alter it's power or its truth. That's the thing about fiction. It can be in every sense a lie, names changed, events altered, fantastical, and yet it can contain essential truths far more profound than any work of "non-fiction." Of course you could argue that all of it is fiction, more or less. I would. That's another rant for another blog.

I find a connection with a new friend -- the filmmaker Guy Maddin. He tells me, "If you can find the story about Guy's third birthday party and the monkey, you need to. It's hilarious." David has rubbed elbows with Guy. He's probably heard the story from Guy's lips, as opposed to second-hand. It may be an apocryphal tale in every way --hidden, esoteric, and spurious -- but that doesn't alter it's power or its truth. That's the thing about fiction. It can be in every sense a lie, names changed, events altered, fantastical, and yet it can contain essential truths far more profound than any work of "non-fiction." Of course you could argue that all of it is fiction, more or less. I would. That's another rant for another blog.Saturday, January 30, 2010

Writing Our Lives As Fairy Tales

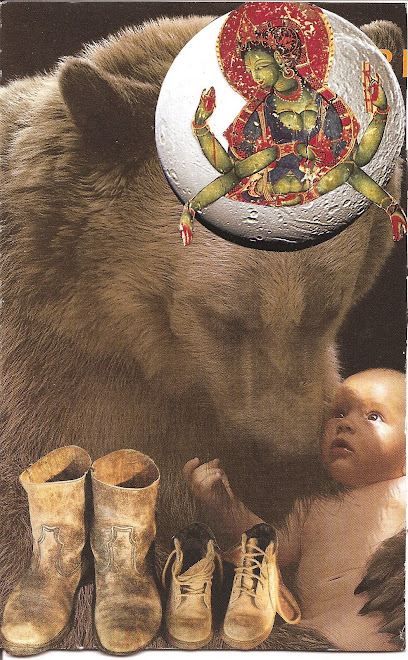

My first attempts at fairy tales occurred when I was quite young and often were a current retelling of the tale. Sometimes around my forties I received a bag of pictures from my mother, actually from my grandmother's stash, ones my mother allowed me. Some were school pictures, mine and hers, some were snapshots of my life and hers, the places where they intersected, the places they didn't. I began writing the stories of those pictures, my own private fairy tales. What follows was my first attempt. I think they lack a certain universality. They are my attempt to tell my history but it is a clumsily, constructed past.

My first attempts at fairy tales occurred when I was quite young and often were a current retelling of the tale. Sometimes around my forties I received a bag of pictures from my mother, actually from my grandmother's stash, ones my mother allowed me. Some were school pictures, mine and hers, some were snapshots of my life and hers, the places where they intersected, the places they didn't. I began writing the stories of those pictures, my own private fairy tales. What follows was my first attempt. I think they lack a certain universality. They are my attempt to tell my history but it is a clumsily, constructed past.

Happily Ever After

The story begins with once upon a time, as all good stories must. There is a princess of course from a far off land, a lovely creature with skin the color of European gold and hair the dense brown of Turkish coffee. Her eyes too are brown, deep and glittering, and there’s something in them that reminds you of the exotic place she comes from. Her scent is heady. You catch the faintest hint under the perfume she wears, spicy and mysterious, unlike anything you know. And though her mouth forms the words of your language, her foreign voice turns them nearly musical. She’s tiny, barely an armful, and when she dances, she comes alive.

There is a prince too, young and full of promise, as most princes are. He’s moved through the world always as if he’s owned it, and for most of his young life it seems he has. Yes, he’s handsome, in the kind of way that disarms a woman, boyish but with a sensual promise that clings to his mouth and eyes. He wants with a ferocity that startles any that encounter it and not once has the object of his desire denied him. Now he wants her, this mysterious princess from far-off lands.

They meet where tradition dictates princes and princesses should, at a ball. Perhaps that’s what makes their story so engaging; it resonates with the elements of countless other fairy tales, stretching back as long as people have been dreaming of happily ever after. No matter how often she hears it told, the girl never tires of it. She’s watched similar fictions unfold upon the screen so often she can close her eyes and see the shot of what was once one, now two, riding into the sunset, music swelling, camera tightening in upon glowing faces, then slowly fading to black. And even knowing the true ending having lived it herself, she still can’t help believing the hype. There’s something so seductive in thinking of happiness as an achievable state, a place one can claim permanent residency, a final destination.

She’s never seen a picture of that particular night, although she has seen one of their wedding just three months later. In it her mother wears a simple satin gown like cream against her skin and a shoulder length veil topping black-coffee curls. She looks impossibly young, her face still carrying a certain vagueness, as if not quite sure what her outcome will be. She smiles, joyous and a bit tentative. She’s accomplished something amazing and she’s not so sure now if it was wise to take such risks, to pin her future on someone still so much a stranger. But there is something too in that face, a fierce longing for adventure and she has gotten that, ten-fold. She will leave the warm, vibrant land of her birth and make a new home halfway across the world in a place of brief delirious summers and bitter, snowy winters,

Her father, dressed in an Air Force uniform, seems just as young. His face is more firmly set. He’s lived a bit and the man he is to become has already taken hold and is molding him in his image. He smiles broadly as befits one so close to achieving his desires. There is nothing tentative in that face; it is full of hunger and the promise of satiation. His eyes tell a different tale though, round, slightly startled, a little glassy. He’s caught in the spell of this strange place he’s found himself. The sights and sounds and smells of an unfamiliar land have invaded him, weaved themselves into his blood and bones and he can’t leave without taking something of it with him. She is that something embodying everything exotic and lovely about this country that’s touched him but can never be his. Through her he will hold it close, bury himself in its foreign charms and remember that time when he was potential and not actuality.

That night though, the one where it all began, her mother wore a dress of sapphire blue and pearls around her neck, not the work of a fairy godmother but borrowed finery nonetheless and, therefore, nearly as romantic. Her father must have come in uniform. He wouldn’t have had anything formal to wear and somehow it fits, he wearing this marker of his difference to set him apart. Her grandmother had accompanied that young vital crowd as chaperone which is how the girl learned the particulars so vital to her own existence. From either of her parents, the prince and princess, she heard nary a word, both mute about the joy of their coming together although much more garrulous about the anger and hurt that came later.

“They never asked me to chaperone,” her grandmother confides, "and who can blame them? I was young too, once. Who wants her mother there when she’s dancing in the arms of handsome young men? But that night they could find no other, and so I went.”

The old woman pauses as always, a soft smile tugging at her generous mouth, a mouth made for it so the smile slides easily from initiation to completion. Her eyes grow smoky with memories. This is the part the girl likes best, when her grandmother travels back in time, drawn by the past and her body sways to the rhythm of old waltzes until you can almost feel the pulse of them echo in your own body, see the dresses swirling in vibrant circles of color, everything punctuated by the laughter of those too young to worry about happily endings.

“Was she beautiful?” The same question every time, but then this is part of the ritual and expected. Her grandmother shakes herself from her reverie, a little disoriented. Her smile deepens, falling into well-worn grooves, and she resumes her story.

“With that dark curly hair hanging loose down her back and that skin gleaming against the dark blue? Of course she was beautiful.”

The girl lets her fingers find her face, tracing by tips the hills and plains there. Where is her beauty? As the daughter of prince and princess, charming and beautiful, surely she should have inherited something. Yet if it exists in her it’s more than skin deep, she thinks, for she has looked in the mirror but never seen any resemblance to the fairy tale creature of the story, too much of her father residing in her features turning every foreign mystery into something prosaic.

“You will be as beautiful as every young girl when she is full of promise and there are men to adore her.” She watches her granddaughter’s face, the doubt that claims it, and laughs the dark laughter of a foreign tongue. “You don’t believe me? Wait. You’ll see. Though you do not look like her, there will be men that find you lovely. Some men look with this,” she would say patting her heart with her palm, “as well as with their eyes.”

“So she’s dancing in her dress of sapphire blue?” the girl prompts, eager for the story to continue. At fifteen she’s too wrapped in despair about her appeal; everything moves so slowly, she emerges from childhood at a snails’ pace while her peers sprint past. The future is tomorrow, and she knows it will bring no changes. The rest is fiction, too far from now to mean anything.

“Believe.” her grandmother laughs. “Some day I will look from heaven and see a man deeply in love with my most beautiful granddaughter, and I will remember this day and smile.” The girl shivers, the words rushing along her skin, and she almost believes the truth of them.

“She danced and danced that night,” the woman continues, returning to the story, her voice filled with memories. She’s there, living it again, and the girl finds she envies this magic of age, this ability to straddle the past and present. She only has now, her past not far enough to inspire nostalgia and her future barely conceivable. “Not one dance did she sit out. She loved the movement, the spinning without rest surrounded by music, held in a young man’s arms.”

The girl tries to imagine this wild motion, the endless turning until the world becomes a blur of color, a rush of sensation, a breathless escape into delirium. She’s never danced like this in the arms of a man, although she would like to. Her gifts though do not lie in grace or beauty. She will have to look elsewhere for whatever in her will draw what she is already hungry for, the first taste of love.

“And then?” the girl urges, because she can’t wait any longer but wants the story to speed to it’s conclusion. It won’t of course, for her grandmother’s a born storyteller with the gift of drawing out a tale, building the tension, toying with her listeners until they beg for release.

“Your father must have been watching. I noticed him, of course, what woman wouldn’t, sitting at one of the corner tables with his friends. There were many like him stationed nearby, but few that came to the dances. I knew then that he was a gentleman.” With this, the woman sighs. She clears her throat a little, looking at her granddaughter meaningfully. “I’m not sure I can go on,” she croaks a bit hoarsely. “Storytelling is thirsty work.”

The girl unfolds herself from her usual position, knees clasped tightly to her chest, and dashes to the kitchen. She grabs a glass from the cupboard and fills it with exactly four ice cubes, more would be wasteful as her grandmother has told her, and less would hardly show respect. She runs the tap until the water turns cool, then fills the glass. As quickly as she can without spilling, she returns to the guestroom. Her grandmother takes the glass with a grateful smile, patting the girl’s cheek and praising her in the soft lyrical sounds of Greek. The meaning of the words hardly matters, although the girl recognizes them as endearments; the smile alone would be worth the effort for her grandmother is a woman who understands the importance of smiling and meaning it. Every time her mouth moves in an upward curve, you see it reflected in her eyes. It makes all the difference. The girl lives with smiles that hang on the face like pictures. They might be beautiful, those painted smiles, but the real thing captivates with its authenticity.

“Much better. You are a sweet girl. Now where was I?”

“My father?”

“Ah yes. A gentleman, as I said. He knew better than to ask her for a dance. He came to the mama. A smart man. You get that from him, I think.”

The girl has resumed her position, rolled tight in a ball of awkward adolescence, the only way she feels comfortable, her most vulnerable parts protected. Yes, this will be her story, a mind instead of beauty, school instead of dances. And she wonders what kind of tale this will be and who will tell it to her child when the time comes. It has never been a story her mother has understood. Assuming there is a story, a prince to her princess, a child that follows. Everything seems doubtful at this age when every look in the mirror gives lie to happily ever after. The grandmother clears her throat one more time, calling the girl back from her reveries, from a nebulous future and a barely formed present. When she’s sure of the girl’s attention, she continues.

“ ‘Bonsoir, madame’ he said in halting French. I made him wait a bit before I answered. Let him sweat. They must never think it’s too easy or they lose interest. I answered him in English,” she laughs. “I could tell he didn’t know much French. His accent was atrocious. But you should have seen his smile. It could light up a room and when he turned it on you, you almost believed yourself blessed.”

The young girl’s hands again rise to her face. She feels her nose which is a mixture of her grandmother’s and her father’s, too long, sitting oddly in a her small face. Her eyes too are the same blend, foreign darkness embracing softer brown. Nothing of the princess exists in her daughter’s features or body either for that matter. Not the merest hint of grace, nor lissome frame meant for dancing, nor golden-toned skin. Crooked fingers are her only legacy, attached to strong capable hands. She is no fairy tale figure, no sprightly beauty, but built for this world and for the work required to make a place in it.

“Your daughter, madame, is the most beautiful girl I’ve ever seen,’ he told me.” The woman frowns a bit. It’s not going quite the way she wants it to. Instead of diversion, the story brings sadness. What once delighted, now brings pain. She offered this tale to the girl eight years ago trying to teach her the magic of her origins in a world rocked by divorce. Now she wonders at the wisdom of this. Everything has become a comparison in which the girl always falls short. She returns to the story because now she’s committed and tries to reclaim the enchantment it once held for both of them.

“How do you know she’s my daughter I asked him. He gave me that smile, the one that seemed like the sun itself. He was generous with those smiles, your father, bestowing them on everyone.” The girl marvels always at this description, This is not the man she calls father; once maybe, but not in her lifetime.

“’Why she could be you ten years ago,’ he answered. I laughed at this outrageousness, me with my white hair and wrinkles and old woman’s body looking like that fairy creature spinning wildly on the dance floor. Bless him,” she muses softly, “letting me believe it might be true. A charming man. A prince. How could I resist him? How could she? So I introduced them.”

“And they fell in love,” the girl whispers, “in the space of an evening.”

“They fell in love,” her grandmother replies, shaking her head, “though such things hardly seem possible outside of books and films.”

“Maybe they aren’t,” the girl says so softly the old woman can’t be sure anythingwas said at all. She decides to let it go. She returns to Athens soon and by the time they see one another again two years from now, this will be old news. If only the girl would talk. But her granddaughter has learned to keep her own counsel, necessary given the volatility of this household. The silence keeps her safe and the old woman has no right to take it from her.

“Three months later, they married.” She hands the girl a black and white photograph in a delicate silver frame. She carries it with her always, this and the most recent school picture of her only grandchild.

“They look happy,” the young girl muses.

“They were,” her grandmother assures her. “Then and later when you were born. Maybe it was the move to California that changed things.”

The girl says nothing, though she knows full well the troubles began long before that move. They are the predominant memories of her childhood -- the raised voices, the angry tears, the sound of breaking china and slamming doors. Let her grandmother keep her fantasies. Having lost her own so young, she recognizes this is the most precious gift she can give the aging woman. They sit for a while silent, each lost in thought, remembering the story never ends with marriage or the birth of a child. It continues, until death do them part.

“I suppose I should get dinner started,” the woman says at last, rising stiffly from the edge of the bed. “I could use some help.”

“In a minute,” the girl replies. Her grandmother nods. The girl in her way is as stubborn as her mother, insisting on following her own path, recklessly traveling places best left unexplored. She knows too much, this child, never a child really, at least not since seven when her father left and the world as she knew it changed forever. There’s no reasoning with her. You can only let her go where she must and hope for the best. The woman leaves her only grandchild and wishes she could do more.

The girl sprawls on her grandmother’s bed, staring at the small picture in a delicate silver frame, the only evidence she has ever seen of her parents’ joy. Once they looked like this. Once they delighted one another. Once the future stretched like the road before Snow White and her Prince, straight, smooth, bathed in sun-gold light. It is hard to reconcile her memories with these two so filled with promise. The eager prince bears only a facile resemblance to the man, face filled with anger and resentment, voice speaking cruel words no one should hear. And the princess, so lovely in her hopefulness, looks nothing like her mother, matching the man word for word, dark voice bitter like Turkish coffee. The hand resting gently on the soft swell of the bride’s hip seems so kind, unlike the one raised to strike, stopping just in the nick of time. And hers, cradling a bouquet of hothouse flowers are positively peaceful, no relation to the ones flinging china furiously against the wall. At what point, the girl wonders, did they realize how it would be between them? Was it that first time the man left with a slammed door and the threat of abandonment hanging heavy in the air? And when did they at last give up on the dream of happily ever after? Was it that last time he stormed from the house, leaving the woman sobbing in a child’s arms?

Carefully she places the picture on the night table. She loves it desperately, but can hardly bear to look anymore at the satin and lace promise of that moment, sun reaching like hands to paint church doors in panels of light, everyone dressed in hopeful smiles. What lesson does one take from such a picture, she wonders, for she is always looking for patterns and lessons, afraid of history repeating itself? How does one reconcile that shining moment with what came after? And what does it say of love, that it begins in such a fever and ends with her father sitting in the dark beside her, explaining why he has to leave?

Her mother married again, this time choosing with head instead of heart. The princess, once vague in her desires, had grown more sharply focused. She bided her time, found her prize, and held on tight, holding still, as though any moment he might slip away. She is queen, but of a dwindling kingdom. Her stepson has a year left at home and it is clear to all that he will flee this place and never return. The daughter appears dutiful and doting, but she too secretly plans her escape. And the princess, now queen, will be left with a smart present but a disappointing future. It will mark her, this discrepancy between what she tasted so many years ago and what she’s settled for, twist her into something no longer beautiful or promising, something without hope. You can see it already in the eyes, the downward tug of the mouth, the back hunched, the body closing in on itself. This is how hags are made and from the bitter harvest of their lives curses are born.

The prince too has moved on, founding a new kingdom of which he is benevolent despot. He remarried the familiar, the taste of home. He has sworn off exotic places even though they still call to him. He has narrowed his domain to what he knows. The daughter visits from time to time but never fully inhabits this world he has created to keep himself safe. She seems more stranger than blood. She may look like him, but retains too much of her mother’s foreignness to ever feel comfortable. The man grows older, passion dwindling like his hunger and desire. And with each passing year, he grows more indistinct. His daughter watches him fade. Soon he will be no more than a ghost of what he was, and then nothing but an echo.

Sometimes it’s more than she can bear these two futures, the weight of them crushing any hope of a third. Yet too much of the two who made her lives within, her mother’s fierce determination and brave hopefulness, her father’s hunger and desire, to make despair a steady state. Conceived as she was when passion and possibility still ruled their lives, she can’t help but believe in her own potential. It keeps her looking forward, expectant, trusting that she can write herself a different story. Rising from the bed, she resists the call of the mirror and that illusive question of fairest of them all. No, there won’t be fairy tales for her … no balls, no Prince Charming. She’ll make her own way, forge her own future, drinking deeply and often of joy and sorrow and the myriad emotions between. Maybe there will be a man who looks deep enough to find the magic of her birthright and if there is no such thing as happily ever after perhaps she will discover her happy medium and find it suits her well. Kitchen smells find their way to the bedroom, reminding her where duty lies. She heads to the kitchen, beginning her story anew.